These are some of my memories and

thoughts from the camp – I tried to be honest with them, and any possible mistakes

in the facts are mistakes of my own.

First impressions

My first impression of Tabanovce

refugee camp was not a shock over the quiet, almost empty camp, with white

containers, dusty roads and some tents. I had already heard from my friend

before arriving that there were more dogs than refugees at the camp. Not an entirely

correct description, but gives you an idea of what I was to encounter; there

were around 30 refugees (and the numbers rose up to 90 overnight) at the time

and probably the same amount of helpers from different organizations. And yes,

a lot of hungry stray dogs. There was nothing to be too shocked about the

refugees eithers; I didn’t see many when I arrived but they all seemed more or

less healthy and well.

One of Tabanovce's many dogs.

The shock I experienced was more

of a cultural type. Once I got into the camp, we were taken straight away to an

air condicioned container, used as an office, and there we stayed with our laptops

and phones, using the wifi and killing the time. A tour around the camp?

Nothing more to see, I was answered. People did not seem very interested in working

with the refugees, even if that was their job (this does not go for everyone working

at the camp but it was a very strong first impression). Before arriving I had thought

that working in a refugee camp had to be a calling for anyone working in there,

that I would find there people who would feel compassion for these people and

would feel happy to be able to be where they were needed. Instead I found out

that to these workers it seemed to be like any other a job, and not even a very

interesting one. I’m not saying they were disrespectful towards anyone, but it

seemed more like an introduction to a local working morals. Whatever the

reason, I was disapponted.

So in the container I had time to

chat, to continue my works from CID and to watch series. Before leaving the camp,

in the afternoon, we might pass by the outdoor kitchen to see if there were any

refugees, and play cards with them for a while. Taking a photo with them was

obligatory as well – to prove that the workers were actually doing something,

and to not to loose followers on social media, as I was told.

I was also told there was nothing

to do – but how does it matter if there are ten refugees instead of one hundred

at the camp? They all value the same and deserve the same attention, even if it’s

”less exciting”. The refugees at Tabanovce had their humanitarian needs

fulfilled – they had clothes, food and a place to sleep. What should’ve been

our job was to take care of their mental health by the means we had to offer,

which were interaction, discussion and play. To release stress and provoke a

smile.

Although, it is also true that

during July, when I arrived, it was constantly so hot in the camp that everyone

preferred to stay indoors in airconditioned spaces. The camp was full of sand

and dust, the sun was so bright it was impossible to look anywhere without

sunglasses and the hotness was something I had never experienced before. The

camp was quiet and sad.

Background on the Macedonian refugee situation

Why were there so few people at

the camp then? The Macedonian borders have been closed since March 2016, so all

the passing through the country (along the so-called ”Western Balkan route”) has

from then on been illegal, or, how we prefer to say, irregular – because no

human being can be illegal. Before the spring 2016 Macedonia was a transit

country. People would take a train, a bike, or walk, from the Greek border in

the South of the country and travel through Macedonia until the Serbian border

in the North. That was the time when, this is what I was told, ”bikes were more

expensive than cars”. The people passing by were taken advantage of in other

ways too, like charging them more for a train ticket, for food and a couple of

euros even for simply taking a shower (three euros is a lot for a shower in a

country where people earn around 200 euros a month on an averige).

I was told that by the summer

2017 there had not been more than 1 to 3 asylum seekers in the country – I cannot

remember the correct number anymore but in any case it was close to zero.

People simply wanted to get to Serbia, and from there usually to Croatia,

Slovenia and to the Western Europe; to Austria, Germany, or where ever.

Furthermore, the camps in

Macedonia are technically not actual refugee camps but merely transit-centers,

so the people are not even supposed to stay there for longer periods of time,

but to be moved to other countries, like Serbia or be deported back to Greece.

A lot of people just try to cross the Serbian border with their smugglers, time

and time again. People arrive to the camp one day and the next morning they

might be gone. Some people of course stay a bit longer, even some months, but

still this somewhat explains the high rotation of people in the camp.

The daily life and routines

”You don’t want to stay there for

too long, believe me”, I was laconically told by my coordinator while waiting

for the taxi to take me and the other EVS volunteers to the camp on my first

day there. This made me angry since the camp was the reason I was in Macedonia

in the first place. But it is true it could be very boring in the camp if you

took it that way, you could be as useless as you wanted to. Only a few refugees

approached us by their own terms and we couldn’t really go searching for them

from their small containers where they sleeped and lived. We were also feeling

unsure if they even wanted to talk with us, although it was clear that there

wasn’t much else to do and that probably they’d be happy to break the routines

of doing nothing – since there was pretty much nothing to do – and communicate

with us.

The communication wasn’t necessarily

that easy either. We didn’t know which ones of them spoke English – and we didn’t

speak any Arabic and there was no interpret either – and their culture was

different, so you didn’t really know what was the best way to act; most of the refugees

in Tabanovce were young men, and most of the volunteers were young women, which

made it somewhat hard and ackward to approach them. It would have been a lot

easier to approach children or women, but even if there were some women

sometimes, they didn’t really leave the containers.

As the time passed, we, however,

got some more experience and courage, and when the ice was broken for the first

time it all got that much smoother and more comfortable – people would start

approaching us, greeting us, telling us about their lives and joining us for a

game of cards, or, later when it wasn’t that hot anymore, volleyball or football

(yes, even I joined sometimes, although I sucked). At some point we had a lot

of Algerians at the camp and I got to practice my forgotten French skills with

them and even translate some conversations with them and other volunteers. It

was empowering for me. All these casual conversations about Erdogan, the

terrorist attack in Finland last summer, youtube videos from someone’s home town.

Little by little we spent less and less time in our containers and more time

together.

Cultural days

Our routines

started changing when another organization working at the camp wanted to

cooperate with the EVS volunteers; as they put it, they had money but not

really a target group, since it was an organization for children but there

weren’t a lot of children in the camp. They wanted to do something for the people

who were at the camp, which was really nice. So we had a meeting where we decided

to start organizing cultural nights, with ”therapeutic cooking” in the

spotlight. This meant that the volunteers would take turns in organizing a day

of activities about our own countries, share some music and videos, and the

main event would be cooking something from our own countries, involving

refugees in the cooking and later sharing the meal together. So this

organization would provide the materials and we would provide the volunteers.

The event

turned out to be more or less of a success. During the first cultural night, a

French one, we were really lucky to have there an Afghan family with two

teenagers and two smaller children. They were really interested in talking with

us (even the 6-year-old spoke very good English!), playing and cooking and I’m

sure we all had such a fun day, even if all the French cakes didn’t succeed

that well. Later there was also a Polish night (turned into an Algerian one), a

Turkish night, a Slovakian night and, of course, a Finnish night, where I got

to make apple pies and salmon breads with some helpful hands, and we watched

videos of Lapland and weird Finnish sports on youtube. During some days it felt

like the whole camp was, if not directly involved, at least trying to be where

the cooking happened; sometimes we only had a couple of people cooking, but

nevertheless, it always felt like it was a nice activity for those involved. I

wish they will continue doing something similar at the camp even now when our

project’s ended and there are no more EVS volunteers.

French cakes in the making!

Dealing with the authorities

Tabanovce of course didin’t come

without bureaucracy or authorities. You can’t just enter the camp (well sometimes

you could, but in theory that’s not how it works), but you need propusnitsa, a permission to enter. This

is why I was only able to enter to Tabanovce camp and not Vinojug, for example.

There were polices by the camp entrance checking everyone coming and going.

In Macedonia the refugees can’t

usually leave the camp either; once you enter, you stay until you’re told

otherwise (or until you decide to take off without a permission). This is why we

couldn’t plan any activities outside the camp, even though they undoubtedly

would’ve done great things for everyone’s spirits and mental health.

There were other restictions as

well, and you can’t always tell why. For example, the organizations couldn’t

teach English at the camp – at least not officially – just because the police said

so. No one knows why. And yes, apparently you do need a permission even for

these kinds of activities.

Once there was a bigger incident

as well, when the police arrived to the camp in the early hours of a Sunday

morning, when everyone was sleeping and there were less eyes to witness what

happened; they arrested around 20 people accused of drug use and some were

deported back to Greece, some were beaten. Just like that.

Refugees or migrants?

True, I’m calling everyone ”refugees”

in this text, but I assume a lot of readers will go and think: are they really

refugees or are they migrants? I’m happy it’s not a decision I need to be

making. I don’t know the backgrounds of all the people at the camp, and as a

volunteer, it wasn’t my duty either. I do know some fragments of their stories,

though. I do know how some of them had traveled through Macedonia hiding dangerously

underneath a moving train. I do know that the Afghan children were caught by

the Serbian police and handcuffed. I saw how afraid they became when, even from

the other side of the fence, they could see a police officer searching the stopped,

empty-looking trains. I do know that many of the young men I met had previously

been detained by the Greek police and held in a prison for several months. I do

know that many of them were traveling alone, like a smiling 17-year-old

Pakistani boy, who had left his home and his family to get to Germany, and who

had already five or six times tried to cross the Serbian border, always getting

caught. And again he was waiting for his smuggler. I do know that a lot of these

people had nice, comfortable lives before, like one older, educated man, a teacher,

who tried to use his time at the camp well by teaching Arabic and painting for

his own enjoyment. And I remember the tired sadness in the eyes of a 14 and

16-year-old brother and sister, who knew they would not be going back home

anytime soon, and not knowing where they would end up and where would their

futures start.

So are these people refugees or

migrants? This experience has made me realize better than ever how superficial

all these kinds of labels are. We try to make sense of people’s origins and

situations by choosing one or another word that should determine if they are

entitled to stay, or if everything they went through was for nothing.

But it’s not like they left their

homes and loved ones for fun.

To conclude

During my time in Macedonia I

felt like I learned so much new, even if nothing was what I expected it to be.

The evolution we went through at the camp was huge, at least for me, and the

acquaintances I made taught me a lot. And even though I wasn’t at the camp more

than twice a week I could use that experience in my other activities at CID;

organizing different refugee-related events and workshops and collecting books

for the camp, for example.

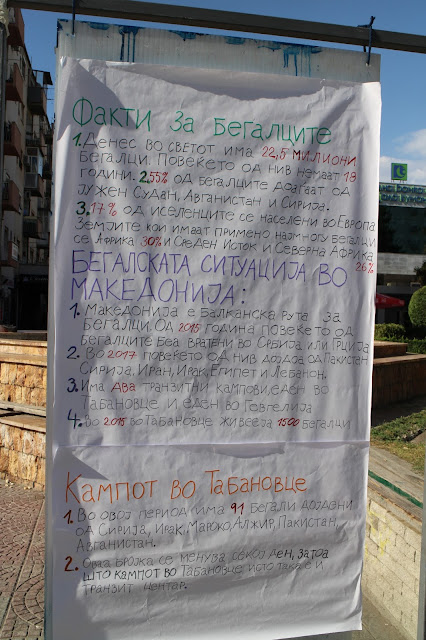

A workshop on refugees for the local youth.

Workshop going on and a poster on Syria in the making!

People at the workshop are concentrating in watching a video on the refugee situation.

I made a poster for the event where we collected books for Tabanovce camp.

Three months was a short time,

and the time just flew away. By the end of my volunteering at the camp I felt

like I had established some good and trusting relations both with the refugees

and the workers at the camp, so it was sad to leave. In the end I did get so

much from the experience and from the people I met.